Congress Members Who Voted Agains Mlk Dat

| |

| Long title | A bill to amend title 5, United States Code, to make the birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., a legal public holiday. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 98th United States Congress |

| Legislative history | |

| |

A United States federal statute honoring Martin Luther King Jr. and his work in the civil rights movement with a federal holiday was enacted by the 98th United States Congress and signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on November 2, 1983, creating Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The final vote in the House of Representatives on August 2, 1983, was 338–90 (242–4 in the House Democratic Caucus and 89–77 in the House Republican Conference) with 5 members voting present or abstaining,[1] while the final vote in the Senate on October 19, 1983, was 78–22 (41–4 in the Senate Democratic Caucus and 37–18 in the Senate Republican Conference),[2] [3] both veto-proof margins.

Prior to 1983 there had been multiple attempts following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. to have a holiday created in his honor with Representative John Conyers introducing legislation in every legislative session from 1968 to 1983.[4] In 1979 a vote was held on legislation that would have created a holiday on the third Monday in January, but it failed to receive two-thirds support and was later rescinded following an amendment changing its date.

While attempts were made to have a federally recognized holiday, numerous U.S. states recognized holidays in honor of King. Connecticut did so in 1973. Illinois adopted a commemoration day in 1969, and made it a paid holiday also in 1973. Other states continued to adopt state holidays up through Utah in 2000.

History [edit]

National [edit]

Prior attempts [edit]

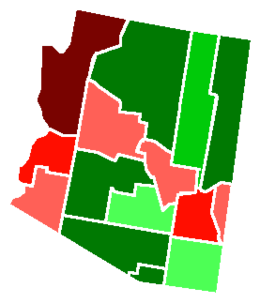

United States House of Representatives vote on the bill

United States Senate vote on the bill

During the 90th Session of Congress following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, Senator Edward Brooke and Representatives John Conyers and Charles Samuel Joelson introduced multiple bills that would create a holiday to honor King on either January 15 or April 4, but none of their bills went to a vote.[5] [6]

In 1971, Ralph Abernathy, the second president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and a close friend of King, submitted multiple petitions to Senator Adlai Stevenson III asking for a national holiday honoring King on his birthday to be created.[7] On February 10, 1971, Senators George McGovern and Jacob Javits introduced a bill in the Senate to recognize King's birthday as a national holiday and issued a joint statement in support of it, but the bill failed to advance.[8] In September 1972, Representative Conyers introduced another bill in the House along with 23 co-sponsors; this was approved by the House Judiciary committee but was not voted on by the full House.[9] [10]

On September 28, 1979, Representative Conyers introduced another bill to create a federal holiday in honor of King, and on October 19, Representative John Joseph Cavanaugh III stated that the U.S. House Committee on Post Office and Civil Service was planning to report the bill to the House floor.[11] [12] On October 23, the bill was reported to the House floor, but Conyers later had the bill delayed on October 30 as he felt that the bill would not reach the two-thirds vote needed for passage, without the addition of amendments that could weaken the bill.[13] [14] Representative Robert Garcia served as the floor manager of the bill and on November 13, the House voted 253 to 133 in favor of the bill, falling short of the two-thirds vote needed for passage.[15] [16] The House voted to amend the bill to move the date of the holiday from Monday to Sunday by a vote of 207 to 191 on December 6, but the bill was rescinded by its sponsors and the Congressional Black Caucus later criticized President Jimmy Carter for not being supportive enough of the bill.[17]

Passage [edit]

On July 29, 1983, Representative Katie Hall introduced a bill to recognize the third Monday in January as a federal holiday in honor of King.[18] On August 2, the House voted 338 to 90 in favor of the bill, passing it on to the Senate.[19] During the Senate deliberation on the bill, Senator Jesse Helms attempted to add amendments to kill the bill and distributed a 400-page FBI report on King describing him as a communist and subversive, leading Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan to throw the report on the ground and refer to it as garbage.[20] [21] Senator Ted Kennedy accused Helms of making false and inaccurate statements, causing Helms to attempt to have Kennedy punished for a violation of rules that prohibit senators from questioning each other's honor. Senate Majority Leader Howard Baker only made Kennedy replace the word "inaccurate".[22] The Senate rejected an attempt to kill the vote by a vote of 76 to 12 on October 18 and later approved the bill by a vote of 78 to 22 on October 19.[23] President Ronald Reagan signed the bill into law on November 2, 1983, and on January 20, 1986, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was celebrated as a federal holiday for the first time.

Congressional vote [edit]

| 1979 U.S. House vote:[24] | Party | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| Yes | 213 | 40 | 253(58.3%) |

| No | 33 | 100 | 133(30.6%) |

| Not Voting | 30 | 18 | 48(11.1%) |

| Vacant | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Result: Failed | |||

| 1983 U.S. House vote: | Party | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| Yes | 249 | 89 | 338(77.9%) |

| No | 13 | 77 | 90(20.7%) |

| Not Voting | 4 | 2 | 6(1.4%) |

| Vacant | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Result: Confirmed | |||

| 1983 U.S. Senate vote: | Party | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| Yes | 41 | 37 | 78(78%) |

| No | 4 | 18 | 22(22%) |

| Not Voting | 0 | 0 | 0(0%) |

| Vacant | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Result: Confirmed | |||

State [edit]

Alabama [edit]

In 1973, Coretta Scott King asked the Alabama Legislature to create a state holiday in her husband's memory on the second Monday in January and Representative Fred Gray, a former civil rights activist, submitted a law to create the holiday according to Coretta's wishes, but it was unsuccessful.[25] Hobson City, Alabama's first self-governed all-black municipality, recognized King's birthday as a town holiday in January 1974.[26]

The Montgomery County Commission voted 3 to 2 in favor of giving its employees a yearly holiday in honor of King on December 22, 1980. John Knight and Frank Bray were the first black people to serve on the commission after being inaugurated in November and voted in favor with Joel Barfoot while Mack McWhorter and Bill Joseph voted against it.[27] However, on January 5, 1981, the commission vote 4 to 1 in favor of changing it from a yearly holiday to a one-time observance.[28]

In February 1981, Governor Fob James sent his legislative program to the Alabama legislature which included a plan to decrease the amount of state holidays from 16 to 12, but would also give state employees the option of taking one day off for non-recognized state holidays that included King's birthday or the birthday of any other statesman.[29] On February 13, 1981, Representative Alvin Holmes introduced a bill to create a state holiday in honor of King, but nothing came of it.[30] On September 14, the Mobile County Commission approved a resolution to create a holiday in honor of King alongside an existing holiday honoring General Robert E. Lee with Douglas Wicks, the only black commissioner, submitting and supporting the bill and Jon Archer opposing it due to him favoring reducing the amount of county holidays.[31] In December the Montgomery County Commission voted 3 to 2 against giving county employees a paid holiday in honor of King with Joel Barfoot, Mack McWhorter, and Bill Joseph against it and John Knight and Frank Bray for it.[32]

In 1983, the all black Wilcox County Commission voted to give county employees a holiday for King's birthday while choosing to not observe Alabama's three Confederate holidays honoring Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Confederate Memorial Day as well as Washington's birthday and Columbus Day.[33] Representative Alvin Holmes created another bill that would combine Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis' birthday for a holiday in honor of King, but later submitted another bill that would only combine a holiday honoring King alongside Robert E. Lee.[34] [35]

On October 21, 1983, Governor George Wallace announced that he supported Holmes' bill to combine Lee and King's birthday holidays.[36] The legislature didn't take action until 1984 when the Alabama House of Representatives voted unanimously in favor of the bill, passed the Senate Governmental Affairs Committee with all six members in favor, passed the Alabama Senate, and Wallace signed the bill into law on May 8, 1984, recognizing Lee-King Day.[37] [38] [39] [40]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| 1984 | 75 | 0 | 75 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| 1984 | 26 | 4 | 30 |

Alaska [edit]

On April 4, 1969, a resolution honoring King was submitted on the anniversary of his death, but the resolution was rejected by a vote of 10 to 8 in the Senate.[41] Following the federal recognition of Martin Luther King Jr. Day a bill was introduced in the Alaska legislature to recognize it on January 15, 1987, and Governor Bill Sheffield declared it as a holiday on January 20.[42] [43] However, state employees were still required to work on the day leading to a union lead lawsuit that was ruled in their favor and the state was ordered to give $500,000 to its employees for overtime pay.[44]

Arizona [edit]

Senator Cloves Campbell Sr. introduced a bill on January 15, 1971, to recognize King's birthday as a state holiday, but it failed to advance.[45] In January 1975, a bill was introduced in the senate to recognize King's birthday as a state holiday, and passed the Government and Senate Rules Committees and was passed by the Arizona Senate, but failed in the Arizona House of Representatives.[46] [47] [48]

In December 1985, Caryl Terrell asked Tempe's city council to recognize King Day, but it was rejected by the Finance and Personnel Procedures committees.[49] On January 18, 1986, 1,000 people marched from the University of Arizona to El Presidio Park to honor King and in support of the recognition of Martin Luther King Jr. Day along with members of Tucson's city council.[50] On January 20, 1986, 5,000 people marched in support of King Day in Phoenix and heard speeches given by Mayor Terry Goddard and Governor Bruce Babbitt who criticized the state legislature for not declaring King's birthday as a state holiday.[51]

On February 7, 1986, the Government Senate Committee voted 4 to 3 in favor of advancing a bill that would create a state holiday in honor of King on the third Monday in January while derecognizing Washington and Lincoln's holidays.[52] On February 19 the senate voted 17 to 13 in favor, but Speaker of the House James Sossaman removed the bill from the agenda after multiple Republicans representatives complained about the bill.[53] [54] The bill was brought back into the house's agenda, but Sossaman stated that it would most likely be defeated and the house voted 30 to 29 against the bill on May 9, 1986.[55] [56] Babbitt circumvented the state legislature and declared the third Monday of January as Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a state holiday via executive order on May 18, although only executive office employees would receive a paid holiday.[57] [58] However, Attorney General Robert K. Corbin stated that the governor did not have the power to declare state holidays and only the state legislature could do so although Babbitt stated that he would not rescind his proclamation and would only do so after a legal challenge.[59] [60]

| Arizona Martin Luther King Jr. Day Amendment | |||||||||||||||||||

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Secretary of State of Arizona[61] | |||||||||||||||||||

During the 1986 gubernatorial election former state senator Evan Mecham ran on a platform that included the removal of the holiday that was established via executive order by Babbitt and narrowly won the election due to vote splitting between Democratic Carolyn Warner and William R. Schulz, who had initially run in the Democratic primary, but after dropping out and reentering was forced to run an independent campaign.[62] [63]

On January 12, 1987, Mecham rescinded Babbitt's executive order causing Arizona to become the only state to de-recognize Martin Luther King Jr. Day.[64] The following day presidential candidate and civil rights activist Jesse Jackson met with Mecham at a joint press conference after meeting for twenty minutes and asked him to reinstate the holiday, but Mecham refused and instead called for a referendum on the issue.[65] 10,000 people marched in Phoenix to the state capitol building in protest of the action on January 19.[66] [67] On May 28, 1987, Norman Hill, president of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, gave a speech in Tucson at the state's AFL-CIO convention where he stated that unions should tell conventions to boycott Arizona and stated that Mecham's decision "caters to bigotry and encourages polarization (of the races)".[68] The de-recognition resulted in $20 million in tourist business being lost due to multiple organizations canceling their conventions in protest, although some, like the Young Democrats of America, kept their conventions in Arizona.[69]

On January 19, 1988, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted 5 to 4 in favor of sending a proposal that would let voters decide whether to create a paid holiday in honor of King on the third Monday in January or an unpaid holiday on a Sunday, but the bill was rejected in the Senate.[70] [71] Mecham was removed from office by the senate on April 4, after an impeachment trial for obstruction of justice and misuse of government funds. On April 14, the Senate Government Committee voted 5 to 4 in favor of a bill that would create a holiday in honor of King and combine Washington and Lincoln's holidays, but the Senate voteed 15 to 14 to reject the bill.[72] [73]

Following the failure of the state legislature to pass a bill creating a state holiday for King, Governor Rose Mofford put forward three options that she would look into: issuing the same executive order Babbitt had issued, wait until after the elections to see if there would be a more friendly makeup towards a King holiday, or wait for a special legislative session to include a King holiday in the plan.[74] Mofford later stated that she would wait until after the elections to attempt to create a King holiday.[75] Due to the failure of the governor and state legislature to create the holiday, another movement to boycott Arizona was created with support from Jesse Jackson and Democratic delegates supporting it and planning to perform a demonstration outside of the Democratic National Convention.[76]

The Arizona Board of Regents voted unanimously on September 9, 1988, to create a paid King holiday at the three state universities that would give 20,000 of the state's 40,000 employees a paid holiday.[77] Arizona State University later chose to end its observation of President's Day and replaced it with the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday.[78]

On January 16, 1989, 8,000 people marched in Phoenix in support of the creation of a holiday in honor of King with Governor Rose Mofford, Goddard, and House Minority Leader Art Hamilton speaking.[79] On February 2, the state house voted in favor of a bill creating a paid state holiday, but Senate President Bob Usdane did not take action on the bill until March 30 when he sent it to the Government Senate Committee where it died in committee.[80] [81] Democratic members of the House included the creation of a holiday inside an economic development bill, but the Commerce Committee voted 7 to 6 to separate the bills.[82]

Another bill was created in the Senate that would end Arizona's observation of Columbus Day in favor of King Day and it passed the Senate Judiciary Committee with 6 to 3 in favor. The bill was passed by the Senate and House and signed by Governor Mofford on September 22, 1989.[83] [84] [85] However, on September 25 opponents of the holiday filed with the Secretary of State to collect signatures to force a referendum on the recently passed bill and submitted enough signatures in December.[86]

On March 13, 1990, the NFL had its annual meeting in Orlando, Florida, and one of the items on its agenda was to determine a host city for Super Bowl XXVII. Among the cities being considered was Tempe, and Arizona civil rights activist Art Mobley was sent to the meeting to make sure that the Arizona ballot initiative was a talking point at the discussion. The vote was conducted and Tempe was awarded the game, but committee chairman and Philadelphia Eagles owner Norman Braman warned that if the King Day ballot initiative went against adoption of the holiday, the NFL would pull the game from Arizona and move it somewhere else.[87]

The bill eliminating Columbus Day was titled as Proposition 301 and another bill was passed by the legislature that would combine Washington and Lincoln's Birthdays and create a King Day was titled as Proposition 302. On November 6, 1990, both referendums were defeated with Proposition 301 being defeated in a landslide due to more effort being spent on Proposition 302 which was narrowly defeated by 50.83% to 49.17%. In March 1991 the house and senate passed a bill that would place a referendum on the creation of a King state holiday onto the 1992 ballot in an attempt to keep the Super Bowl in Arizona.[88] On March 19, 1991, NFL owners voted to remove the 1993 Super Bowl from Phoenix due to the rejection of both referendums. It was estimated that the state lost at least $200 million in revenue from Super Bowl lodging and $30 million from the numerous convention boycotts.[89] On November 3, 1992, Proposition 300 was passed with 61.33% to 38.67% and Super Bowl XXX was later held in Tempe, Arizona in 1996.

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1986 | 29 | 30 | 1 | 60 |

| 1989 | 35 | 24 | 1 | 60 |

| 1989 [a] | 37 | 21 | 2 | 60 |

| 1991 | 40 | 11 | 9 | 60 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1975 | 16 | 13 | 1 | 30 |

| 1986 | 17 | 13 | 0 | 30 |

| 1988 | 14 | 15 | 1 | 30 |

| 1989 [b] | 17 | 11 | 2 | 30 |

| 1991 | 25 | 4 | 1 | 30 |

Referendum Results

| 1990 Proposition 301 Results[91] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Votes | Percentage | ||||

| No | 768,763 | 75.36% | ||||

| Yes | 251,308 | 24.64% | ||||

| Totals | 1,020,071 | 100.00% | ||||

| 1990 Proposition 302 Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Votes | Percentage | ||||

| No | 535,151 | 50.83% | ||||

| Yes | 517,682 | 49.17% | ||||

| Totals | 1,052,833 | 100.00% | ||||

| 1992 Proposition 300 Results | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Votes | Percentage | ||||

| Yes | 880,488 | 61.33% | ||||

| No | 555,189 | 38.67% | ||||

| Totals | 1,435,677 | 100.00% | ||||

Arkansas [edit]

In February 1983, the Arkansas House of Representatives and the Arkansas Senate before being signed into law by Governor Bill Clinton allowing state employees to choose to take a holiday off on Martin Luther King Jr., Robert E. Lee, or their own birthday.[92] [93] In 1985, the state legislature voted to combine King and Lee's birthdays and stayed combined until March 14, 2017, when Governor Asa Hutchinson signed a bill separating the holidays.[94]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1991 | 66 | 11 | 23 | 100 |

Connecticut [edit]

A bill to recognize King's birthday as a holiday was passed by both the Connecticut House of Representatives and Connecticut Senate in 1971, but was vetoed by Governor Thomas Meskill, who had initially supported the bill, citing the cost of having another paid holiday with it being around $1.3 million.[95] [96] [97] The bill was reintroduced by Representative Irving J. Stolberg in 1972, and it passed in the senate again, but was defeated in the house.[98] [99] Governor Meskill issued a proclamation in 1973 recognizing King's birthday and Representative Maragaret Morton, the first black women in the state assembly, later introduced a bill to create a holiday in honor of King, but it was shelved by the General Law Committee as they felt that Meskill would veto it again.[100] [101] [102]

Supporters of the King holiday created a petition and it had received enough signatures from legislators in February 1973 to force public hearings on a bill for the holiday. Although the law initially put forward by the petition failed, an amended version passed the house 124 to 17 in favor and the senate with unanimity, and Governor Meskill signed it into law on June 14, 1973, making Connecticut the first state to recognize a holiday in honor of Martin Luther King Jr.[103] [104] [105] [106]

On March 4, 1976, Governor Ella Grasso stated that she would support moving the holiday from the second Sunday to January 15. The state legislature passed a bill to change the holiday's date and make it a paid holiday, and Grasso signed the bill on May 4, 1976, making the holiday fall on January 15 and as a paid holiday for Connecticut's 40,000 state employees.[107] [108] [109] [110]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| 1971 | 97 | 41 | 138 |

| 1972 | 56 | 86 | 142 |

| 1973 | 124 | 17 | 141 |

| 1976 | 121 | 24 | 145 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| 1971 | 25 | 9 | 34 |

| 1972 | 17 | 16 | 33 |

| 1976 | 32 | 4 | 36 |

Illinois [edit]

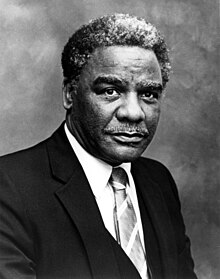

Harold Washington, a state representative from the 26th district, introduced a bill to create a holiday in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1969.[111] The House executive committee voted to advance the bill, both state legislative chambers voted in favor of the bill and Governor Richard B. Ogilvie signed the bill creating a commemorative holiday in honor of King that would allow school services to be held in his honor.[112] [113] [114]

Washington proposed a bill in 1970 to make the commemorative holiday a paid legal holiday but was unsuccessful. Washington reintroduced the bill in 1971, and it passed the house with 121 to 15 in favor and the senate with 37 to 7 in favor, but was vetoed by Governor Ogilvie.[115] [116] [117] The Chicago Public Schools system started to observe King's birthday in 1972.[118]

In January 1973, Washington, Susan Catania, and Peggy Martin reintroduced the bill in the Illinois House of Representatives.[119] On April 4, the House voted 114 to 15 in favor of the bill, the Illinois Senate later voted in favor of it as well, and Governor Dan Walker signed the bill on September 17, 1973.[120] [121]

Kentucky [edit]

On January 15, 1971, Mayor Leonard Reid Rogers of Knoxville declared a holiday in honor of King in the city.[122] In February 1972, state Senator Georgia Davis Powers introduced a bill that would create a state holiday in honor of King, but it did not make it through the committee although they told Davis to offer an amendment to a holiday bill currently in the legislature.[123] [124] However, Davis was absent when the bill came to the senate, but was able to offer an amendment to another holiday bill although the bill was defeated after her amendment passed.[125] [126]

On January 15, 1974, Powers and Representative Mae Street Kidd proposed bills to create a state holiday in honor of King and both bills passed through each chambers' committees.[127] [128] The Kentucky Senate and Kentucky House of Representatives passed the bill and on April 1, 1974, and Governor Wendell Ford signed it into law.[129] [130] [131] Although the King holiday was not officially paired with Robert E. Lee Day both days would occasionally fall on the same day whenever the third Monday in January was on the 19th.[132]

Governor Julian Carroll declared the first King Day in Kentucky in 1975, but state employees were not given the day off with Carroll citing an economic crisis as the reason.[133]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| 1974 | 50 | 6 | 56 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| 1974 | 30 | 1 | 31 |

Maine [edit]

On February 13, 1986, a bill to create a paid holiday in honor of King was defeated in the house, but was later modified to make it optional and passed the Maine Senate and Maine House of Representatives before being signed by Governor Joseph E. Brennan and going into effect on July 16, 1986.[134] [135] [136]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1986 | 77 | 61 | 13 | 151 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1986 | 24 | 5 | 6 | 35 |

Massachusetts [edit]

In 1974, members of the Massachusetts Black Caucus introduced a bill to recognize Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday as a state holiday, but it died in committee.[137] However, the bill was revived by state Senator Joseph F. Timilty who changed it to a half-holiday that would allow businesses to stay open, but governmental offices would close.[138] The bill passed both the House and Senate before being signed into law by Governor Francis Sargent on July 8, 1974.[139] [140]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1974 | 160 | 53 | 27 | 240 |

Missouri [edit]

On January 7, 1971, Mayor Alfonso J. Cervantes of St. Louis signed into law a bill that would create a city holiday in honor of Martin Luther King on January 15.[141]

New Hampshire [edit]

On February 11, 1999, Jesse Jackson spoke in Portsmouth where he stated that he was considering a presidential run and asked for New Hampshire to recognize a state holiday in honor of King.[142] On April 8, 1999, the Senate voted in favor of a bill renaming Civil Rights Day to Martin Luther King Jr. Civil Rights Day and was later passed by the House before being signed by Governor Jeanne Shaheen on June 7.[143]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1999 | 212 | 148 | 40 | 400 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1987 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 24 |

North Dakota [edit]

Governor George A. Sinner appointed a commission in 1985 to coordinate the state's federal observation of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, but state employees were not given the day off.[144] In 1987, a bill was introduced to recognize it as a state holiday and was passed by the House and Senate before being signed by Governor Sinner on March 13, 1987.[145] [146] [147]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1987 | 64 | 39 | 3 | 106 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1987 | 27 | 26 | 0 | 53 |

Ohio [edit]

On January 14, 1975, Cincinnati's city council recognized a city holiday in honor of King and approved a resolution in support of a statewide holiday bill created by state Senator Bill Bowen.[148] Bowen's bill passed the Senate and House before being signed into law by Governor Jim Rhodes on May 2, 1975.[149] [150] [151]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1975 | 57 | 33 | 9 | 99 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1987 | 24 | 5 | 4 | 33 |

Wyoming [edit]

Representative Rodger McDaniel introduced a bill in 1973 that would create a holiday in honor of Martin Luther King Jr., but nothing became of the bill.[152] Another bill creating a King holiday was introduced in 1986 by Representative Harriet Elizabeth Byrd, but it was rejected.[153] Governor Mike Sullivan signed an executive order in 1989 that would have Wyoming observe a holiday in honor of King only for 1990.[154] On January 2, 1990, the Albany County Commission voted to observe King Day for only 1990.[155]

A bill creating a holiday in honor of King that would end Wyoming's observation of Columbus Day was introduced in 1990. An attempt to change its name from Martin Luther King Jr. Day to Wyoming Equality Day was defeated by a vote of 32 to 29 although it was later renamed as Martin Luther King, Jr./Wyoming Equality Day as a compromise to allow it to pass.[156] [157] [158] The bill passed the House and Senate and Governor Sullivan signed the bill into law on March 15, 1990.[159] [160] [161]

Legislative votes

| House votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1990 | 48 | 16 | 0 | 64 |

| Senate votes: | Vote | Total votes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not voting | ||

| 1990 | 21 | 9 | 0 | 30 |

Timeline [edit]

| Timeline of Passage of Martin Luther King Jr. Day | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | State | Action | Percent of states |

| April 4, 1968 | TN | Death of Martin Luther King Jr. | 0.00% |

| June 18, 1971 | CT | Vetoed | 0.00% |

| September 28, 1971 | IL | Vetoed | 0.00% |

| June 14, 1973 | CT | Recognized | 2.00% |

| September 17, 1973 | IL | Recognized | 4.00% |

| April 1, 1974 | KY | Recognized | 6.00% |

| July 8, 1974 | MA | Recognized | 8.00% |

| 1975 | RI | Recognized | 10.00% |

| May 2, 1975 | OH | Recognized | 12.00% |

| May 4, 1976 | CT | Amended date and paid | 12.00% |

| 1977 | NJ | Recognized | 14.00% |

| 1977 | MI | Recognized | 16.00% |

| 1977 | LA | Recognized | 18.00% |

| 1978 | MD | Recognized | 20.00% |

| 1978 | PA | Recognized | 22.00% |

| 1978 | SC | Recognized | 24.00% |

| 1979 | MO | Recognized | 26.00% |

| 1982 | WV | Recognized | 28.00% |

| 1983 | WI | Recognized | 30.00% |

| March 7, 1983 | AR | Recognized | 32.00% |

| 1983 | CA | Recognized | 34.00% |

| 1983 | NC | Recognized | 36.00% |

| November 2, 1983 | USA | Recognized Federal Holiday to begin in 1986 | 36.00% |

| 1984 | VA | Recognized | 38.00% |

| 1984 | TN | Recognized | 40.00% |

| 1984 | NY | Recognized | 42.00% |

| 1984 | MN | Recognized | 44.00% |

| 1984 | GA | Recognized | 46.00% |

| 1984 | DE | Recognized | 48.00% |

| May 8, 1984 | AL | Recognized | 50.00% |

| 1985 | CO | Recognized | 52.00% |

| 1985 | KS | Recognized | 54.00% |

| 1985 | NE | Recognized | 56.00% |

| 1985 | OK | Recognized | 58.00% |

| 1985 | OR | Recognized | 60.00% |

| 1985 | WA | Recognized | 62.00% |

| 1986 | VT | Recognized | 64.00% |

| 1986 | IN | Recognized | 66.00% |

| May 18, 1986 | AZ | Recognized | 68.00% |

| July 16, 1986 | ME | Recognized | 70.00% |

| 1987 | MS | Recognized | 72.00% |

| 1987 | NV | Recognized | 74.00% |

| 1987 | NM | Recognized | 76.00% |

| January 12, 1987 | AZ | Derecognized | 74.00% |

| January 20, 1987 | AK | Recognized | 76.00% |

| March 13, 1987 | ND | Recognized | 78.00% |

| 1987 | TX | Recognized | 80.00% |

| 1988 | HI | Recognized | 82.00% |

| 1988 | FL | Recognized | 84.00% |

| 1989 | IA | Recognized | 86.00% |

| 1990 | ID | Recognized | 88.00% |

| 1990 | SD | Recognized | 90.00% |

| March 15, 1990 | WY | Recognized | 92.00% |

| November 6, 1990 | AZ | Referendum | 92.00% |

| November 6, 1990 | AZ | Referendum | 92.00% |

| 1991 | MT | Recognized | 94.00% |

| November 3, 1992 | AZ | Referendum | 96.00% |

| June 7, 1999 | NH | Recognized | 98.00% |

| 2000 | UT | Recognized | 100.00% |

| March 14, 2017 | AR | Separated holidays | 100.00% |

Notes [edit]

- ^ Bill eliminating Columbus Day.

- ^ Bill eliminating Columbus Day.

References [edit]

- ^ "TO SUSPEND THE RULES AND PASS H.R. 3706, A BILL AMENDING TITLE 5, UNITED STATES CODE TO MAKE THE BIRTHDAY OF MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., A LEGAL PUBLIC HOLIDAY. (MOTION PASSED;2/3 REQUIRED)".

- ^ "TO PASS H.R. 3706. (MOTION PASSED) SEE NOTE(S) 19".

- ^ Dewar, Helen (October 20, 1983). "Solemn Senate Votes For National Holiday Honoring Rev. King". The Washington Post . Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ Crawford-Tichawonna, Nicole. "Years of persistence led to holiday honoring King". USA TODAY. No. January 12, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- ^ "Brooke Wants 'King Day'". Fort Lauderdale News. April 9, 1968. p. 12. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dr. King Day Proposed". The Morning Call. April 8, 1968. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Presenting petitions". The Pantagraph. January 18, 1971. p. 14. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senators Urge Dr. King Holiday". Arizona Daily Star. February 11, 1971. p. 56. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bill Asks Holiday For Martin King". Arizona Daily Star. September 28, 1972. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King holiday bill". Tucson Daily Citizen. September 30, 1972. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Actions - H.R.5461 - 96th Congress (1979-1980): A bill to designate the birthday of Martin Luther King, Junior, a legal public holiday. | Congress.gov | Library of Congress". 1979.

- ^ "King day bill advanced". The Lincoln Star. October 20, 1979. p. 8. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King holiday bill awaits". The Roswell Daily Record. October 31, 1979. p. 19. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House Delays Vote for U.S. Holiday on Kings Birthday". The Los Angeles Times. October 31, 1979. p. 4. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Martin Luther King national holiday bill set back in House". The Independent-Record. November 14, 1979. p. 17. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House rejects shortcut to creating new holiday". The Courier-Journal. November 14, 1979. p. 4. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House rejects shortcut to creating new holiday". The Atlanta Constitution. December 7, 1979. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Another chance for King's holiday". The Atlanta Constitution. July 30, 1983. p. 22. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday Wins In House, Goes To Senate". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. August 3, 1983. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The politics of a holiday". The San Francisco Examiner. October 6, 1983. p. 30. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King holiday was decades in the making". Times News. January 20, 2020. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020.

- ^ "Jesse Helms and MLK". Salon. January 17, 2011. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020.

- ^ "King Day vote on tap". Daily News. October 19, 1983. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Martin Luther King Jr. Day 1979 House Vote" (PDF). Congressional Record. November 13, 1979. p. 32175.

- ^ "Want Alabama To Honor King's Birthday". The Dispatch. March 16, 1973. p. 5. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Stringer proclaims King Day Tuesday". The Anniston Star. January 12, 1974. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "County approves King holiday". The Anniston Star. December 23, 1980. p. 8. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Birmingham to observe King holiday". The Selma Times-Journal. January 6, 1981. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "James proposes holiday for Dr. King's birthday". The Selma Times-Journal. February 7, 1981. p. 8. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Holiday Bill Introduced". The Selma Times-Journal. February 13, 1981. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mobile Approves King Holiday". Alabama Journal. September 15, 1981. p. 13. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "County Commission Nixes King Holiday". Alabama Journal. December 22, 1981. p. 9. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King holiday proclaimed". The Selma Times-Journal. January 25, 1983. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Holmes ask combination". The Selma Times-Journal. April 26, 1983. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bill would unite Lee, King days". The Montgomery Advertiser. October 21, 1983. p. 29. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Wallace Calls King Holiday 'Appropriate'". Alabama Journal. October 21, 1983. p. 5. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House OKs House bill". The Selma Times-Journal. April 6, 1984. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King holiday bill OK'd". The Montgomery Advertiser. April 12, 1984. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Legislature OKs King state holiday". The Selma Times-Journal. May 3, 1984. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Governor Signs King Holiday Bill". Alabama Journal. May 9, 1984. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Alaska Resolution On King Defeated". Fairbanks Daily News-Miner. April 5, 1969. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lawmakers Honor Martin Luther King". Daily Sitka Sentinel. January 16, 1986. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'King Day' Proclaimed In Alaska". Daily Sitka Sentinel. January 20, 1986. p. 8. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Overtime Pay OK'd For Federal Holiday". Daily Sitka Sentinel. July 30, 1986. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Holiday Bill Offered". Tucson Daily Citizen. January 16, 1971. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Proposed King Holiday Brings Sharp Exchanges". Arizona Daily Sun. January 30, 1975. p. 16. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Committee Endorses 'King' Day". Arizona Daily Star. January 30, 1975. p. 60. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Memorial Passes Senate In Tight Vote". Arizona Daily Star. February 12, 1975. p. 20. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tempe kills bid for paid King holiday". Arizona Republic. January 20, 1986. p. 77. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1,000 Tucsonans march to honor memory of Martin Luther King". Arizona Daily Star. January 19, 1986. p. 21. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "5,000 march in Phoenix to honor memory of fallen civil-rights leader". Arizona Republic. January 21, 1986. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senate panel favors state holiday for King". Arizona Daily Star. February 7, 1986. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senate kills bill to repeal vehicle-sales tax". Arizona Republic. February 20, 1986. p. 9. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Holiday Bill Delayed". Arizona Daily Sun. February 28, 1986. p. 15. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Holiday Bill Advances". Arizona Daily Sun. May 9, 1986. p. 8. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Arizona House defeats King holiday plan". Tucson Citizen. May 10, 1986. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Babbitt to Declare State Holiday in Honor of King". Arizona Daily Sun. May 18, 1986. p. 5. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Babbitt declares state holiday for King". Arizona Republic. May 19, 1986. p. 13. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Babbitt to go ahead on King holiday". Tucson Citizen. June 3, 1986. p. 15. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Babbitt invites suit over decision to create Martin Luther King Day". Arizona Republic. June 4, 1986. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "State of Arizona Official Canvas – General Election – November 3, 1992" (PDF).

- ^ "The Timeline of Passage of Martin Luther King Jr Day". January 15, 2018. Archived from the original on March 13, 2019.

- ^ "King holiday to be rescinded". Arizona Daily Sun. November 6, 1986. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pupils". Arizona Republic. January 16, 1987. p. 24. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jackson asks Mecham to restore King holiday". Arizona Daily Star. January 14, 1987. p. 42. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "March on Capitol". Arizona Republic. February 6, 1988. p. 137. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mecham problems called peril to party". Tucson Citizen. January 1, 1988. p. 22. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Convention boycott of state urged". Arizona Republic. May 29, 1987. p. 5. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Young Democrats keep convention in Phoenix". Arizona Republic. July 13, 1987. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Judiciary panel sends King bill to full Senate". Arizona Daily Star. January 20, 1988. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senate defeats proposal for voters to pick holiday". Arizona Daily Sun. February 26, 1988. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "State Senate panel OKs King Day plan". Tucson Citizen. April 14, 1988. p. 29. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King holiday is jettisoned by senators". Arizona Republic. July 1, 1988. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mofford mulls ways to tackle King holiday". Arizona Republic. July 7, 1988. p. 15. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Group split over state boycott plan". Arizona Daily Sun. July 12, 1988. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Convention to hear Arizonans on King day issue". Tucson Citizen. July 16, 1988. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Regents approve paid King Day at state universities". Arizona Republic. September 10, 1988. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "ASU to honor King, drop Presidents Day". Arizona Republic. December 4, 1988. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'We want a holiday!' 8,000 march to state Capitol to seek King tribute". Arizona Republic. January 17, 1989. p. 5. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House approves paid King holiday". Tucson Citizen. January 17, 1989. p. 27. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Usdane assigns King Day bill to committee". Arizona Daily Star. March 30, 1989. p. 18. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "GOP-controlled House committee cuts King holiday from economic-aid bill". Arizona Daily Star. April 20, 1989. p. 17. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senate panel OKs King holiday in lieu of Columbus Day". Arizona Daily Star. September 21, 1989. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "GOP relents, King Day OK'd". Arizona Republic. September 22, 1989. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mofford signs King holiday, hails 'proud day'". Arizona Daily Star. September 23, 1989. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Referendum petitions put paid state King holiday on hold". Tucson Citizen. December 22, 1989. p. 56. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "When Arizona lost the Super Bowl because the state didn't recognize Martin Luther King Jr. Day". March 22, 2017. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017.

- ^ "King Day officially on ballot". Arizona Republic. March 13, 1991. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Holiday's rejection costing millions now". Arizona Daily Sun. January 15, 1991. p. 4. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "How They Voted". Arizona Republic. July 3, 1988. p. 31. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1990 election results" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-08-30.

- ^ "HB 214 House bill passed". The Times. February 15, 1983. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "HB 214 House bill passed in Senate". The Madison County Record. March 3, 1983. p. 19. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Arkansas Splits Its Holidays For Martin Luther King Jr. And Robert E. Lee". NPR. March 20, 2017. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019.

- ^ "Senate Passes 'King Day' Legal Holiday". Hartford Courant. May 28, 1971. p. 25. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Holiday Voted As king Tribute". The Bridgeport Post. June 4, 1971. p. 43. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Black Leaders Attack Veto of Dr. King Holiday". The Bridgeport Post. June 18, 1971. p. 40. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bill To Honor King With Holiday Passes State Senate by 1 Vote". Hartford Courant. March 3, 1972. p. 31. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bill to Make Holiday Of King's Birth Killed". Hartford Courant. March 10, 1972. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Day Proclaimed For Dr. King". Hartford Courant. January 15, 1973. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mrs. Morton Files Bill On Holiday for Dr. King". The Bridgeport Post. January 21, 1973. p. 14. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Holiday Bill Is Shelved". The Bridgeport Post. February 7, 1973. p. 19. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bill for Holiday To Honor King Will Get Hearing". The Bridgeport Telegram. February 15, 1973. p. 63. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House Votes Bill to honor King with Sunday Holiday". The Bridgeport Telegram. May 19, 1973. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sunday Holiday Bill Is Voted To Honor Dr. King in State". The Bridgeport Post. May 24, 1973. p. 16. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Meskill Signs King Day Bill". The Bridgeport Post. June 15, 1973. p. 9. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Holiday Plea Cheered at Capitol". Hartford Courant. March 5, 1976. p. 35. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House Backs Jan. 15 To Honor King". Hartford Courant. April 22, 1976. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jan. 15 Holiday Is Voted; Governor Due to Approve". The Bridgeport Telegram. April 29, 1976. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jan. 15 Set As King Day". Hartford Courant. May 5, 1976. p. 22. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Newcomers' Welfare Curbs Voted". Chicago Tribune. April 10, 1969. p. 33. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House Approves Holiday Honoring Martin Luther King". The Decatur Herald. April 30, 1969. p. 46. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Create Holiday To Honor Martin Luther King". The Dispatch. June 19, 1969. p. 20. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Holiday". The Pantagraph. October 7, 1969. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bill Would Schedule Dr. King Observance". The Jacksonville Daily Journal. May 22, 1971. p. 6. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senate Pass MLK Jr. Day". The Jacksonville Daily Journal. July 1, 1971. p. 26. Archived from the original on January 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "How Harold Washington fought for MLK Day — and paid the price". January 14, 2018. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020.

- ^ "Chicago Public Schools Observe MLK Jr. Birthday". Chicago Tribune. July 5, 1973. p. 23. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "States Offices To Be Closed On King's Birthday". Mt. Vernon Register-News. December 14, 1973. p. 10. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dr. King Holiday BIll Goes To Senate". The Dispatch. April 5, 1973. p. 20. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Holiday Honors Martin Luther King". The Edwardsville Intelligencer. September 18, 1973. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Memory". Messenger-Inquirer. January 16, 1971. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "MLK Holiday Bill Introduced in Kentucky". The Courier-Journal. February 15, 1972. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "MLK Holiday Bill Fails In Committee". The Courier-Journal. March 8, 1972. p. 13. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Amendment Not Filed". The Courier-Journal. March 16, 1972. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Holiday Bill Dies in Senate". Messenger-Inquirer. March 17, 1972. p. 15. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1974 MLK Introduced". The Courier-Journal. January 16, 1974. p. 15. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Holiday to honor Dr. King advances". The Courier-Journal. February 28, 1974. p. 13. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "National NAACP backs local telethon". The Courier-Journal. March 5, 1974. p. 12. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "SB 78 Passes House". The Courier-Journal. March 21, 1974. p. 18. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Martin Luther King Jr. honored by state holiday". The Courier-Journal. April 2, 1974. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Monday to be a dual holiday". The Courier-Journal. January 17, 1998. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Memorial to Dr. King". The Cincinnati Enquirer. January 9, 1975. p. 38. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Maine bill spurs racism debate". The Boston Globe. February 23, 1986. p. 35. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House approves bill to honor King". Maine Campus. February 25, 1986. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 25, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "AN ACT to Change Martin Luther King Day from a Special Observance Day to a State Holiday" (PDF). Maine Legislature. July 16, 1986.

- ^ "Black caucus pushes bid for holiday honoring Dr. King". The Boston Globe. May 1, 1974. p. 79. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senate revives bill for King half-holiday". The Boston Globe. June 14, 1974. p. 4. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Martin Luther King Day advances". The Boston Globe. June 26, 1974. p. 5. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "State Holiday Made". The Lincoln Star. July 9, 1974. p. 21. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Establishes Day For Dr. King In St. Louis". Freeport Journal-Standard. January 9, 1971. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jackson weighs presidential bid". Freeport Journal-Standard. February 12, 1999. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "N.H. governor signs MLK holiday into law". The Boston Globe. June 8, 1999. p. 24. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Employees to work on King's birthday". The Bismarck Tribune. October 28, 1985. p. 20. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Not everyone likes King". The Bismarck Tribune. January 21, 1987. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senate votes to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr". The Bismarck Tribune. March 5, 1987. p. 9. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "State designates annual King day". The Bismarck Tribune. March 14, 1987. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Holiday Gets Boost". The Cincinnati Enquirer. January 15, 1975. p. 16. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bill For Martin Luther King Holiday Protested". The Tribune. February 20, 1975. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Here's how they voted". The News-Messenger. April 25, 1975. p. 10. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King day bill signed". The Journal Herald. May 3, 1975. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "King Bill Introduced". Casper Star-Tribune. January 31, 1973. p. 17. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House refuses King holiday, lottery". Jackson Hole News. February 26, 1986. p. 24. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jackson stays clear of Wyo politics during Cheyenne visit". Casper Star-Tribune. April 21, 1989. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Albany employees to observe King holiday". Casper Star-Tribune. January 5, 1990. p. 19. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "House vote restores King's name onto bill". Casper Star-Tribune. March 9, 1990. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'Equality Day' added to title". Casper Star-Tribune. March 10, 1990. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Liz Byrd, First Black Woman in Wyoming's Legislature". May 24, 2015. Archived from the original on January 2, 2020.

- ^ "'King Equality Day' approved by House". Casper Star-Tribune. March 11, 1990. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Senate concurs with House on King bill". Casper Star-Tribune. March 13, 1990. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Wyoming governor signs bill creating paid King holiday". Casper Star-Tribune. March 16, 1990. p. 12. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

parrisjustruescan.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passage_of_Martin_Luther_King_Jr._Day

0 Response to "Congress Members Who Voted Agains Mlk Dat"

Postar um comentário